Why does everything look infantilized?

On CPG, infantile branding, and overproduction

If you’re like me, you have been bemoaning that they “just don’t make things like they used to.” I’ve heard myself speak these words while opening the drawers of 100% wood media consoles at antique stores, caressing the fabric of a heavy wool Burberry skirt in my grandmother’s closet, and considering the weight of a vintage sterling silver dessert spoon. In my head, yesteryear was a time when the average American had access to and wore mass-produced yet well-made pieces from J. Crew and Lord & Taylor (not Uniqlo and Shein), purchased items for their utility from trusted brands… and companies respected consumers, who also respected themselves.

Two separate, but related, trends in the consumer economy have caught my eye and signal doom for the environment, the consumer’s experience, and trust between the consumer and the brand.

** DISCLAIMER: I am not saying that the mentioned or pictured brands are bad or sell bad product. I like some of them!

It is true that our lives have been simplified, for better or worse, by the “app-ification” of society. You use an app to call a car to the airport, to order dinner when you don’t feel like cooking, to hire a handyman to install your AC unit, to find someone to pet-sit, to do all your job functions (the Teams/Slack/Outlook trinity), to track your health, to organize your schedule, to track your spending, to check where your friends or kids are, to….. etc etc etc. Like the Industrial Revolution, this “app-ification” or onslaught of the mobile internet age freed people up to allow them to focus on more monumental work.

TREND 1: INFANTILE BRANDING

A clean, user-friendly, tech-y brand has emerged for almost every possible need. To order your medicines, use hims or hers. Need to go to the dentist? Head to tend, the VC-backed chain of dental practices. Renter’s insurance? Get lemonade! Want a sweet treat? crumbl lets you order right from the app! Even sweetgreen calls itself a tech company.

The technology itself isn’t bad, and I am a believer in its ability to elucidate processes and needs that were once unnecessarily confusing or expensive. The trend I want to parse is the homogenous brand look and language of these companies.

When D2C and consumer technology companies were starting out in the ~late 2010s, they wanted to communicate that they were tech-driven and “innovative”. It made sense to do this through branding, and apparently this puffy, lowercase, sans-serif logo with a decidedly non-threatening aura was the graphic design trend du jour for these companies. Everything was lowercase, copy was “cool” and nonchalant, and the websites and app interfaces spoke to you like you were 5.

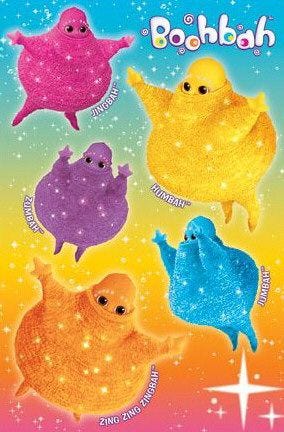

This combination of a logo that is the typeface embodiment of a Teletubby or a Boohbah, “cool” copy, and dumbed-down interfaces and consumer communication being at the core of every tech-first consumer company’s visage for the past ~8 years is dumbing down the consumer. A company presenting itself like an inoffensive high school kid with a heavy AP schedule likely won’t present great service or product, and in return the consumer won’t ask much of it.

Annie Dabir of Dabbling summed up some of the effects of this well:

“After returning several Casper mattresses, spending months waiting for my Byte aligners to arrive, and my AWAY luggage being rejected at the gate, the designer in me began to associate this *look* with bad service. And it wasn’t just the branding, but the names too. Recently, a Tend office popped up in our neighborhood. If I ever dare to set foot in a dentists office again, I don’t want a name like Tend. I asked my husband what he wants in a dentist. He said he wants he wants an old farty name like Regional Dentistry Associates of Eastern Nashville. And they BETTER not have an app to book, we want a nice old southern lady to call us or we are NOT showing up!”

While consumers gain time and ease through this app-ification, they lose the intangibles of experience that these tech-driven companies whittle away: the anticipation of a good meal, a friendly rapport built up over years of confirming appointments with your doctor’s secretary, or a meet-cute while waiting in line at a Midtown lunch place.

This isn’t just about branding. It’s about a cold user experience, impersonal service, and a growing universe of empty brands driven by “tech” to service our every need and want.

TREND 2: YASSIFIED CPG (SPECIFICALLY, FOOD + BEVERAGE)

I hate to use the term yassified, especially because I am criticizing the infantilization of the consumer by companies, but it is too apt.

We all know that olive oil brand, that tinned fish brand, that cereal brand. Consumers saw them placed in the hands of influencers and pushed by the algorithm on Instagram. Then, people walked into the “homewares + provisions” store on their block in Cobble Hill and saw the product IRL, in its green squeeze bottle glory. These “Instagram brands” got their start at the curated retail stores Neil Shankar dubbed “shoppy shops”, places where you “can touch all the products you see on Instagram.” Now, you can find them at Whole Foods, Target, Walmart, and on Amazon.

The popularity of the original yassified CPG consumables like Graza and Fishwife has spawned countless comparable company launches, or, more earnestly, brand activations. They are brand activations because these businesses aren’t revolutionizing anything about the food or beverage they are selling, they are merely manufacturing a shiny new identity and brand universe around it, and bringing THAT to market, often to compete with other lookalikes.

They are betting on the consumer being susceptible to bright colors, flashy packaging, and glitzy marketing. Ideally, they’d mold consumers into possessing a childlike sensibility, grabbing for the candy at the checkout aisle. It’s working, and it’s fueling the creation of brands spun out of the ether, overproducing inferior versions of products that already exist with branding being the sole differentiator.

Manufacturing and scaling these brands has become a science. Identify a consumable in a sleepy category (it’s been done for tinned fish, olive oil, cereal, pickles, etc.), conjure up a fun name and brand universe (or hire Gander to do it for you), market it via what Emily Sundberg calls “smallwashing”, let the algorithm work for you, then let the money roll in. You can infuse your product with some ethos (woke? artisanal? familial? back to basics? better-for-you?) or just let the fonts and colors and IG reels do the talking.

“Successfully marketing a product so that it feels local everywhere is an art. I’ve started calling this crucial step in a product’s development “smallwashing,” i.e., when a brand positions itself as a small business and shows up on shelves as if it were small, even though it has probably been through at least one comfy fundraise and a hotshot General Catalyst VC sits on the board.”

Consumers covet, and they buy, and this encourages the creation of brands following a similar GTM recipe. However, we’re left with a landscape of consumables where nothing is authentic. Consumers think they’re buying into a small brand, one that’s run by fun people who want to revolutionize an overlooked product. More often than not, though, they’re buying into a hollow shell of too much VC money, flashy branding, and find the product is just not that good. Most importantly, it’s often at a higher price point than its regular, run-of-the-mill counterpart.

It is insulting that companies believe they can slap a cute label onto a jar of pickles and have consumers clamoring to shell out twice what they’d pay for a regular jar; but, they can, because people are buying.

Advertising and branding used to be smart. It was witty, cohesive, and most importantly, it respected the intelligence and shrewdness of the consumer it was marketing to.

Infantile brands and yassified products are dumbing down the market with dumb product, ultimately dumbing down the consumer. They appeal to base inclinations to communicate to the consumer that this product, service, or company is at once easy to use, friendly, and maybe even fun and silly. You get a fun and silly dentist and a fun and silly jar of pickles.

Ok, so how’d this happen?

These unprecedented market strategies are creating an infantilized adult consumer. “The role of marketing in the infantilization of the postmodern adult” (Jacopo Bernadini) outlines how over time, adulthood has shifted from an idea to an ideal (Arnett) that is difficult to achieve, moving the target for companies from the adult to the “kidult”, who:

“is easily suggestible, tends to want objects that have no utilitarian purpose, is driven by individualistic, irrational and almost exclusively playful desires, does not take into account the needs of others and does not present substantial diversification in tastes”.

This “kidult” takes “young” to be a lifestyle attitude, rendering it a conscious choice rather than a transitory state. As this state is promoted and sustained by the market and media, the “child” (not literally a child, but the childlike adult) becomes valuable as a consumer in the market and therefore a target for marketers. Bernadini argues that the market not only deviates towards catering to this “kidult” but has found its ideal customer in the kidult, who harbors the irrationally consumerist nature of the child combined with the economic resources and buying power of the adult.

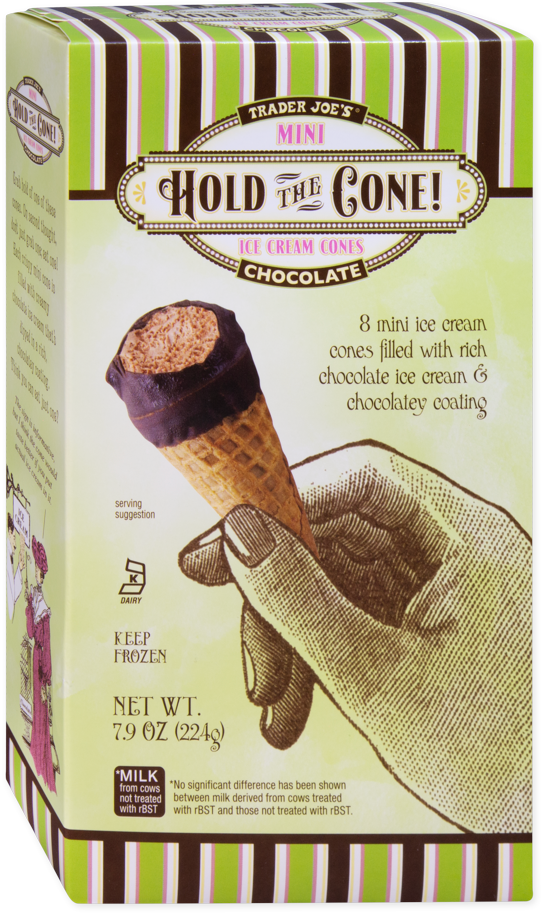

The Trader Joe’s millennial craze is perhaps the most palpable, paradigm-setting example of the market targeting the kidult. Trader Joe’s transformed grocery shopping, a utilitarian and purpose-driven activity, into a quest that tickled consumers’ childlike curiosity via product discovery. Trader Joe’s doesn’t serve you well if you go in with a grocery list comprised of ingredients to make meals (chicken, spinach, salt, good olive oil, etc.) Even if you do go in with a list, most can’t help but walk away with items like “peanut butter brookies”, “Hold the cone! mini ice cream cones”, “cacio e pepe puffs”, or “Gone Bananas! Dark chocolate covered banana slices”. Busy adults could forego planning and preparing actual meals and eat exclusively frozen Trader Joe’s orange chicken or any other of the frozen Lunchables for liberals. TJ’s is a place where the individual branding of each item, often a childhood favorite just slightly touched up, prompts the sale, rather than necessity or quality.

The most obvious, and most dire, outcome of products selling on nothing but branding is the overproduction of lookalikes with differing brand identities. It’s easy to start yet another skincare brand after seeing the success of the Glossier simulacrums at Sephora, or to begin development of a made-to-eat oats company with even more playful marketing. There’s a low barrier to entry to spinning a CPG company out of thin air, thanks to companies like Pietra that handle sourcing, packaging, distribution, fulfillment, and creative.

That leads to both first-time and serial founders (using the word “founder” might be generous in many cases) pumping out consumer brands that are merely cash grabs. Who loses here? The consumer, and the environment. Sustainability is touted as a guiding principle for many “mission-driven” companies, but the irony is the most sustainable thing to do would be to not produce at all, unless the benefit to the consumer plausibly outweighs the environmental harm. Sure, a new indie CPG brand isn’t going to destroy the earth, but death by a thousand paper cuts…

What, then? I am a supporter of enterprise and realize cessation of business or production isn’t ideal. The relationship between founder and consumer needs to be fixed - that can happen via consumers being more discerning, and founders prioritizing the creation of the best products, ones that feel authentic and like they might have a story behind them.

The recipe for a differentiated product is to find white space in the market, solving a consumer need that isn’t met. Founders should strive for this, or further, to create entirely new categories:

“Companies that create new categories, or successfully redesign existing categories, are the ones that ultimately change the world. Along the way, they create exponentially more value for both shareholders and the entire market. Category designers are people and companies that move the world from the way it is, to the way they think it should be.” - Category Pirates

Founders need to engage with real people, not one-dimensional caricatures of our inner children. Founders should pursue smart customers, and smart customers want things that enrich their lives, signal status, and make them happy. To have longevity, those things need to feel authentic, like they’re coming from a real place, not a Williamsburg WeWork.

I really appreciate this article. I studied graphic design in college and during my time as a student I had similar sentiments as what you share. I often disliked how professors didn't challenge my peers enough to design something beautiful that isn't for a screen and without using a computer. Modern design and advertising is not at all what it used to be. Something about the craft has been lost due to the digital prevalence of modern culture. Many people think, "Why put any effort in making a clever ad when people will only "swipe" by it?". Much to think about, and plenty of work to be done to change the tide of the "infant" trend. Thank you for writing about this!

Thank you for verbalizing the weird, haunting feeling I've had when walking into *hip* gift shops that seem to exclusively sell these kinds of products. Everything looks the same, like I'm in some kind of freakish, pastel hall of mirrors.